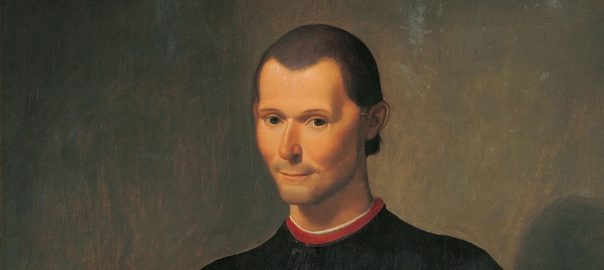

Niccolò Machiavelli, the sixteenth century Italian political theorist, saw history as a recurring pattern of decline and renewal. This stemmed from his view of human society and human nature. Society could never have a natural unity nor could it be based on a shared understanding of the common good. Instead, Machiavelli believed that society is always divided by conflicting interests and all we can hope for is an artificial unity, attained by balancing competing social forces. However, our innate tendency towards selfishness means that we are prone to pushing our own interests too far, undermining any equilibrium that may have been achieved. At this point, decline sets in.[i]

Machiavelli’s view of history can be applied to the contemporary UK. Britain’s political settlement of the last few decades, which can be broadly defined as a commitment to liberal globalisation, is on its way out. Leave’s victory in the 2016 EU referendum is the biggest indicator of this, though we can point to UKIP’s triumph in the 2014 EU parliament election, to Jeremy Corbyn’s election as Labour leader in 2015, and to the rise of the Brexit party as further proof. It’s too soon to say what form a new political settlement will take, but the direction of travel seems to point towards greater cultural conservatism and economic protection.

Machiavelli may also help us understand why this decline has come about. In this respect, it’s important to emphasise that Britain’s political commitment to liberal globalisation wasn’t inevitable. It was neither naturally ordained nor was it the result of a societal-wide agreement. Instead, this commitment reflected the historically constituted preferences of certain social groups.

In broad terms, we can describe these social groups as Britain’s metropolitan middle classes. But a more nuanced approach is offered by the economist Thomas Piketty. He uses the terms “Brahmin left” and “merchant right” to capture both the social composition and primary interests of these groups. By Brahmin left, he means an intellectual elite, people with at least a bachelor’s degree who are vested in a globally oriented cultural liberalism. By merchant right, he means a business elite, individuals with high income and wealth who see a globally oriented economic liberalism as the top priority. These two elites aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive and they have been the main social forces behind Britain’s political embrace of liberal globalisation.

The interests of these social groups are legitimate and should be included within British politics. Machiavelli would certainly have recognised this, though crucially, he would have wanted their influence to be counterpoised by other social forces. Yet herein lies the problem. Until recently, UK politics was dominated by the Brahmin left and merchant right.

The apex of their domination occurred between 1997 and 2015, under the premierships of Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, and David Cameron. During this period, Labour tilted a bit more towards the intellectual elite and the Conservatives a bit more towards the business elite, but Britain’s two main parties effectively converged on a platform of cultural and economic liberalism. That’s why Blairite Labour stressed that Britons should be “prepared constantly to change” and government should take a “light touch” approach to markets.[ii] And that’s why Cameron’s Conservatives helped pass the 2013 Same Sex Marriage Act and further scaled back the role of the state in the economy.

There are a number of reasons why the Brahmin left and merchant right became more politically influential. Firstly, since the 1980s the size and prominence of these social groups has increased due to the expansion of higher education and the financialization of the economy.[iii] Secondly, as I’ve discussed in more detail elsewhere, Britain’s first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system incentivised both Blairite Labour and Cameron’s Tories to court voters from these backgrounds, so enabling the metropolitan middle classes to hold more political sway

Finally, Britain’s rulers in recent times have tended to come from, and share the worldview of, the intellectual and business elites. The leading lights of Blairite Labour were inculcated in a “metropolitan cultural liberalism” and sincerely believed that “markets work best”, and Cameron’s ‘Notting Hill set’ embodied a similar outlook. This organic affinity between Britain’s leaders and the metropolitan middle classes allowed the latter’s interests to gain more political traction. Indeed, Britain’s leaders committed themselves to liberal globalisation largely because this seemed natural and right to them.

But while structural changes, FPTP, and leadership preferences account for the heightened political power of the metropolitan middle classes, these factors don’t explain why these groups came to dominate British politics. Theoretically, Blairite Labour and Cameron’s Conservatives could have promoted elite interests while accommodating the views of other social sectors. Yet for the most part this didn’t happen, with the result that major social forces – most notably the working classes and Middle Englanders – had their voices excluded from the political mainstream. As Machiavelli would have predicted, this disequilibrium stemmed primarily from selfishness. During the Blair-Cameron era, elites came to regard their own interests as absolute and they discounted the interests of others.

A striking example of this selfishness is provided by Blair’s address to the 2005 Labour party conference. In this speech, Blair equated liberal globalisation to a force of nature – like “autumn” following “summer” it was inexorable. This irresistible reality was “indifferent to tradition” and had “no custom and practice”, he said, meaning parochial attachments had to go. He also stated that government protections against the “onslaught of globalisation” were a non-starter, as the “dam holding back the global economy burst years ago”. Britons simply had to be “swift to adapt” and “open, willing and able to change”. At no point did Blair consider that those with alternative cultural and economic interests should be represented. They had to adapt to the elite worldview or be brushed aside by cultural and economic liberalism. Either way they would disappear.

But such exhortations are unrealistic. For Machiavelli, competing interests are a basic feature of society and so those unenamoured with liberal globalisation were always going to fight back. Brexit is the starkest instance of this fightback, driven predominantly by blue collar and provincial voters who want a new settlement based on the nation, more cultural conservatism and more government control of the economy.

But this pushback wouldn’t have been so severe if it wasn’t for elite selfishness. Without this egoism, alternative interests may have been properly represented in the traditional institutions of British politics, allowing the liberal political settlement to be modified from within. Yet with it, elites dominated these institutions, effectively forcing other social groups to pursue their interests via non-traditional means and to challenge the existing order from the outside. UKIP, the EU referendum and the rise of the Brexit party can all in large measure be attributed to this selfishness. So too, albeit to a much lesser degree, can the rise of Corbyn.

So, by pushing its own interests too far, Britain’s liberal elite triggered its own decline. To stick with Machiavelli’s schema, the task before us is to rebalance British politics and affect a renewal. Unfortunately, we still appear to be in the very early stages of that process.

[i] Joseph V. Femia, Machiavelli, in, David Boucher, and, Paul Kelly (eds.), Political Thinkers: From Socrates to the Present, Oxford University Press, 2009

[ii] Gordon Brown, quoted in, Jonathan Hopkin, and, Kate Alexander Shaw, ‘Organized combat or structural advantage? The politics of inequality and the winner-take-all economy in the United Kingdom’, Politics & Society, 44, 2016, pp. 345-371

[iii] Ibid.