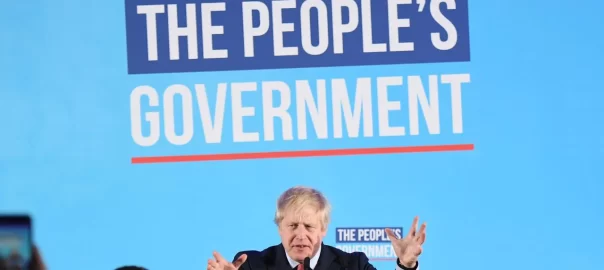

It was only a short while ago that Britain’s working classes were on the rise. Brexit was to a large extent a working class revolt against the status quo, and our ruling elite seemed to get the message: “we will … [shift] the balance of Britain decisively in favour of ordinary working class people”, declared prime minister Theresa May at the 2016 Conservative party conference. May’s calling of a snap election in 2017 led to her party losing its majority in the House of Commons, paving the way for a parliamentary impasse over Brexit. When this impasse was finally broken, working class votes were once again crucial. The December 2019 election saw many traditional Labour constituencies – the so-call ‘red wall’ – turn blue, giving May’s successor, Boris Johnson, an emphatic victory.

Following this victory, many commentators forecast that the Conservatives would become a blue collar party. The academic Philip Cunliffe wrote that “the Tories will now lead a working class revolt to overturn the neoliberal order”. There were solid grounds for thinking this. The Conservatives not only pledged a number of pro-worker policies – such as using post-Brexit state aid and procurement freedoms to revive industry – they also had a material interest in delivering: without the red wall, Labour would have practically no chance of forming a majority government, at least for the time being.

It was for this reason that Keir Starmer, upon becoming Labour leader in April 2020, quickly set about reaching out to the working classes, as shown by the emphasis he placed on patriotism. Though some took umbrage with this approach, arguing that Labour’s “old heartlands [were] gone for good” and that the party should focus on consolidating its support in big cities among young graduates and professionals, these critics ignore basic electoral realities: parties with geographically concentrated vote-shares struggle to win under first-past-the-post.[i] (You could also say that Labour has a historic obligation to rebuild the red wall since the party was founded to protect working class interests.)

By spring 2020, then, both the Tories and Labour had a political interest in, and seemed to be committed to, making life better for the working class. Yet over the last two or so years the policy choices of our rulers have made the working classes worse off.

Continue reading Lockdowns, sanctions, inflation: how Britain’s working classes lost out