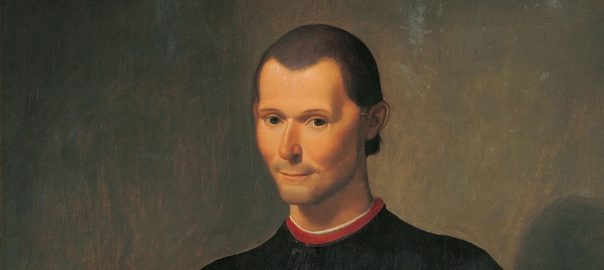

Niccolò Machiavelli, the sixteenth century Italian political theorist, saw history as a recurring pattern of decline and renewal. This stemmed from his view of human society and human nature. Society could never have a natural unity nor could it be based on a shared understanding of the common good. Instead, Machiavelli believed that society is always divided by conflicting interests and all we can hope for is an artificial unity, attained by balancing competing social forces. However, our innate tendency towards selfishness means that we are prone to pushing our own interests too far, undermining any equilibrium that may have been achieved. At this point, decline sets in.[i]

Machiavelli’s view of history can be applied to the contemporary UK. Britain’s political settlement of the last few decades, which can be broadly defined as a commitment to liberal globalisation, is on its way out. Leave’s victory in the 2016 EU referendum is the biggest indicator of this, though we can point to UKIP’s triumph in the 2014 EU parliament election, to Jeremy Corbyn’s election as Labour leader in 2015, and to the rise of the Brexit party as further proof. It’s too soon to say what form a new political settlement will take, but the direction of travel seems to point towards greater cultural conservatism and economic protection.

Machiavelli may also help us understand why this decline has come about. In this respect, it’s important to emphasise that Britain’s political commitment to liberal globalisation wasn’t inevitable. It was neither naturally ordained nor was it the result of a societal-wide agreement. Instead, this commitment reflected the historically constituted preferences of certain social groups.

Continue reading Machiavelli, liberal decline, and Britain’s selfish elite